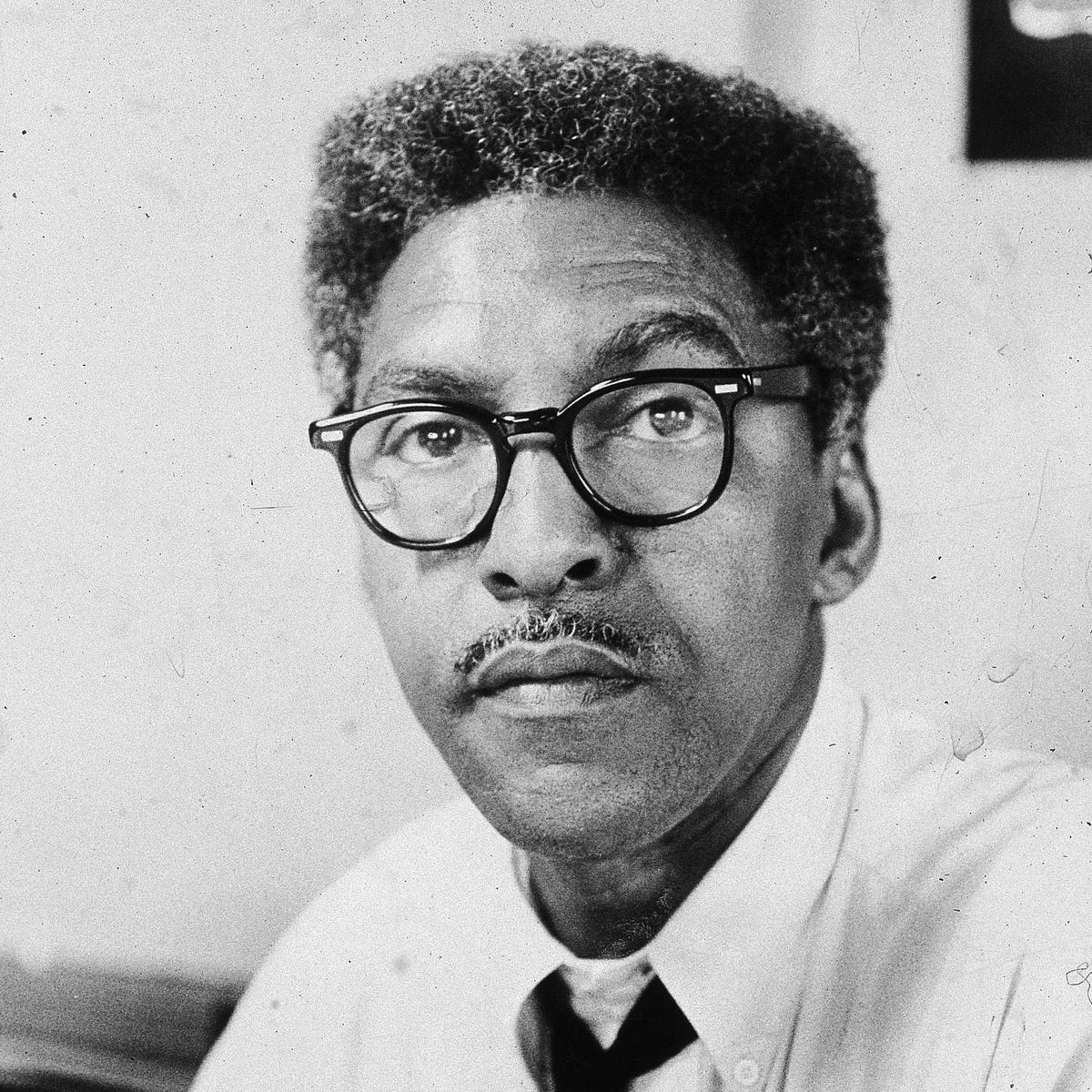

As we continue our journey through Pride month, we seek to honor a somewhat less visible figure in the civil rights and the gay rights movements. Bayard Rustin was born March 17, 1912, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He was raised by his grandparents who instilled in him his quaker values which he said, “were based on the concept of a single human family and the believe that all members of that family are equal.” Through their work with the NAACP, they also gave him their strong sense of social justice. In fact, his grandmother would regularly have W.E.B. DuBois over as her guest.

Rustin was a typical teenager. He liked to write poems and he played on his high school football team. However, it was during that time that he also began to notice his preference to males over females. When he told his grandmother that he preferred to spend time with males rather than females, she simply responded with, “I suppose that’s what you need to do.” It was Rustin’s first documented realizations of his sexuality. He would go on to live his life as an out gay man in a time when the closet was the safest place for a member of the LGBT+ community to be.

After graduating, Rustin attended both Wilberforce University, and HBCU in Ohio, and Cheyney State Teachers College, and HBCU in Pennsylvania. However, he never graduated from either institution. Instead, in 1937, he moved to New York City to study at City College of New York (CUNY), a hotbed for political activism. While there he became an activist participating in protests against segregation. He also joined the Young Communist League for a brief time before dropping out after they tried to force him to quit protesting segregation in the U.S. armed forces.

Rustin remained active throughout the 1930s and 40s. He was instrumental in convincing President Franklin D. Roosevelt to draft the Fair Employment Act which banned racial discrimination in defense industries and federal agencies. Then, in 1941, Rustin was arrested and beaten for refusing to move to the back of the bus during a trip from Louisville to Nashville. Rustin linked that experience to his decision to come out as a gay man stating that if he didn’t he would be aiding the prejudice that was attempting to destroy him because, “to be afraid is to behave as if the truth were not true.”

Although Rustin enjoyed the freedom that came from living his life as an out gay man rather than having to hide it, it came at a price. His life would be drastically altered in 1953 in Pasadena, California where he was caught having sex with another man in a parked car. Although charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, Rustin pled guilty to a lesser charge of “sex perversion,” which today is called sodomy, despite the act being consensual. He spent 60 days in jail and was forced to register as a sex offender. Decades later he would be pardoned by California Governor Gavin Newsome in an effort to correct a “long and reprehensible history” regarding gay men.

In 1956, Rustin traveled to Alabama to lend his support to Dr. King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He remained out of the spotlight but had a strong influence on King and his beliefs. Rustin had met with Mahatma Gandhi years prior, in 1948, and was taught Gandhi’s beliefs of nonviolence which Rustin went on to incorporate into his activism. Rustin went on to teach Dr. King those same principles. During the boycotts, Rustin wrote publicity materials and organized carpools. He also helped King organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1956-1957.

Unfortunately, in 1960, King parted ways with Rustin after Representative Adam Clayton Powell Jr. of New York threatened to spread false stories to the press that Rustin and King were gay lovers if he didn’t drop Rustin from his team. Powell Jr. was angry at the time that Rustin and King were planning a march outside of the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles.

Three years later, in 1963, Rustin and King would reunite after Rustin had been planning a national March to commemorate the centennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation with A. Philip Randolph. When King heard about the idea, he became excited about the notion of a national March. Rustin returned to Alabama to meet with King regarding the march and together they expanded the focus to jobs and freedom. Rustin would go on to play an integral role in organizing and planning the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where King would give his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech.

Rustin continued to spend his life dedicated to activism for both the black and gay communities, often intertwining them. Sadly, on August 24, 1987, Rustin passed away due to complications from surgery. His legacy and his contribution to history will live on in the lives he fought for and changed, and in the principles he taught. Though he had struggles to overcome, he lived his life authentically and unashamed.

References:

Biography (2014). Bayard Rustin biography. Biography.com. https://www.biography.com/activists/bayard-rustin

Brownworth, V. A. (2020). Bayard Rustin: A radical gay icon for our time. Philidelphia Gay News. https://epgn.com/2020/02/26/bayard-rustin-a-radical-gay-icon-for-our-time/

Gates, H. L. (no date). Who designed the March on Washington? PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/100-amazing-facts/who-designed-the-march-on-washington/