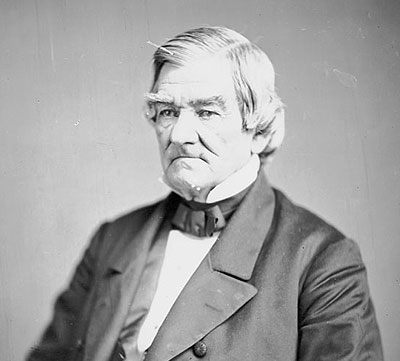

November is Native American and Indigenous Peoples History Month. This month we will be celebrating individuals of indigenous descent who, though often overlooked in history books, have made a great impact on our shared history. This week we kick off the month with Tsan-Usdi, AKA John Ross, an influential Chief of the Cherokee for over forty years, though they might refer to themselves as the Ani’Yun’wiya, the Tsalagi, or the Kituwah.

Ross was born October 3, 1790, in Turkeytown, a town near present-day Centre, Alabama. Interestingly, Ross was born to a Scottish father and a Scottish-Cherokee mother. His father owned a store near Lookout Mountain and used his money to build a school and hire a teacher to ensure his children received a quality education. Although he was only 1/8th Cherokee, he clung to his indigenous roots and witnessed the brutality towards indigenous people that existed on the American frontier towards his people. By 1810 he was already serving his community by acting as a Native agent for his tribe on behalf of the United States.

In 1812, Ross served as a military officer in the War of 1812 where he fought valiantly. Once the war ended, he was elected to the Cherokee National Council where he took on the role as the primary English-speaking member of the tribe in order to communicate the needs of the tribe to representatives of the United States government. He would go on to be elected President of the National Committee in 1819, a role in which he would find himself advocating for his tribe’s inherited rights to Cherokee land which the government actively wanted to acquire. At the time, Georgia was using the Compact of 1802 in which Georgia agreed to give up rights to lands to the west in exchange for the federal government removing the Cherokee people from their lands. Between 1805 and 1833, Georgia held eight separate lotteries to give away traditional Cherokee lands.

Part of fighting back against the land acquisition included the Cherokee Council, of which Ross was a member, adopting their first constitution in 1827 which established three branches of government. In 1828, the Principal Chief, Pathkiller, passed away, and within two weeks, his successor, Charles Hicks, followed suit. As a result, John Ross was elected Principal Chief that same year, and for the next ten years, he fought in courts and tried strategic diplomacy with leaders in D.C. Unfortunately, his efforts during this time were to no avail.

In May of 1830, congress passed the Indian Removal Act. In response, Ross and the Cherokee people hired an attorney who wrote an argument that the Cherokee people should be considered a sovereign nation under the U.S. Constitution and represented them in the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia court case. Sadly, the court did not rule in favor of the Cherokee Nation and refused to hear its complaints against the state citing that the Cherokee Nation was not a foreign nation.

Although he lost in court, Ross continued to fight for the Cherokee people fending off bribes and attacks. At one point, the Senate offered Ross $5 million if his tribe would see roughly 7 million acres of their land. He refused the offer, but while he was in D.C., a posse called the Georgia Guard took his house, seized the printing press of the Cherokee newspaper, and eventually arrested Ross.

Shortly after being imprisoned, a group known as the Ridge party, later the Treaty Party, signed the Treaty of New Echota. The treaty provided the $5 million that Ross was offered, but also charged various fees charged by the U.S. government to the Cherokee government. Although Major Ridge and the group did not have the authority to sign such a treaty and did not have the approval of the tribe, the treaty was seen as official. The resulting Cherokee removal started in 1836. In September or October of that year, some 16,000 Cherokees were marched from their homelands to Indian Territory before one of the worst winters on record. The journey took six months and covered 950 miles. Several more detachments of Cherokee were marched out of their lands in the coming months.

Once in their new land, Ross was instrumental in keeping the tribe together and strong. They passed a new constitution in 1839 and won remuneration from the U.S. government for the long deadly trip they had to take to get there in 1841. Ross passed away in Washington D.C. on August 1, 1866. He was initially buried in Delaware, but his body was returned to Indian Territory a few months later, where he was buried in Park Hill, Oklahoma.

References:

Davis, J. (2020). John Ross: His struggle for homeland and sovereignty. Library of Congress Blogs. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2020/10/john-ross-his-struggle-for-homeland-and-sovereignty/

Dominican University (no date). Cherokee. Dominican University Rebecca Crown Library. https://research.dom.edu/NativeAmericanStudies/cherokee#:~:text=The%20name%20comes%20from%20the,caves.%E2%80%9D%20The%20tribe’s%20original%20name

Moulton, G. E. (no date). Ross, John (1790-1866). The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=RO031

Tikkanen, A. (Ed.) (2023). John Ross: Chief of Cherokee Nation. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Ross-chief-of-Cherokee-Nation

Weiser-Alexander, K. (2021). Chief John Ross of the Cherokee Nation. Legends of America. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-johnross/