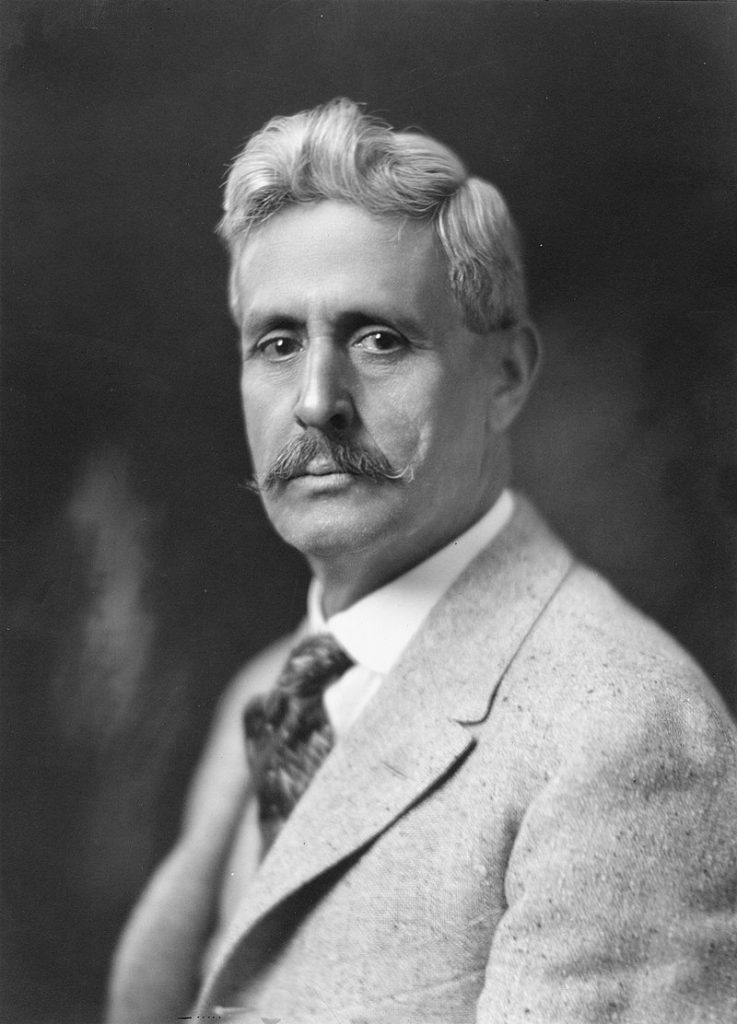

Octaviano Larrazolo was born on December 7, 1859 in El Valle de Allende, Chihuahua, Mexico, but immigrated to the United States at the age of 11 in 1870. Born to an affluent landowning father, Larrazolo grew up in relative comfort learning to read and write at a young age. However, his comfort would not last long. By the mid-1860s, his family was left destitute due predominantly to his parents’ support of Benito Juárez and his revolt against the French occupation of Mexico at the time.

With his parents unable to pay for his education, Larrazolo left home to move to Tucson, Arizona Territory* in the United States under the care of Bishop John Salpointe. Larrazolo hoped to become a priest and attended schools in both Arizona Territory and New Mexico Territory. However, after graduating from St. Michael’s College in Santa Fe in 1876, he began teaching in Texas thanks, in part, to his fluency in both English and Spanish. During this time, he met his wife Rosalia Cobos. They would go on to have two sons, Juan and José, and a daughter, Rosalie.

While teaching, Larrazolo began studying law at night. As he discovered his passion for law, he decided to become an American citizen in preparation for a legal career. On December 11, 1884, at the age of 25, Larrazolo earned his citizenship and by the following year was appointed clerk of the U.S. District and Circuit Courts for the Western District of Texas. In 1888, he was admitted to the Texas bar which would allow him to open more doors in his growing political career. He was elected district attorney for Texas’ 34th Judicial District in El Paso in both 1890 and 1892. However, while working as district attorney, his wife sadly passed away. He would marry María Garcia whom he would go on to have nine more children with.

Larrazolo faced some difficult times politically over the next few years. He ran for the office of Territorial Delegate to the U.S. Congress on three different occasions each time losing to his opponent. While he did come close to winning the final two elections, his position as a Democratic nominee in an area where the majority-Hispanic population leaned Republican proved too much to overcome. In addition, he faced a lack of support from his own party which tended to have an anti-Hispanic view as demonstrated when the party refused to send any Hispanic delegates to New Mexico’s constitutional convention where they ultimately opposed provisions that guaranteed Spanish speakers their civil rights. ** This was particularly disheartening to Larrazolo who insisted the Bill or Rights the convention was working on safeguard the political, civil, and religious rights of those of Spanish and Mexican descent. While some of the provisions were included, the experience led him to leave the Democratic party in 1911 to join the Republicans.

For much of the early 1900s, however, Larrazolo was routinely criticized and attacked by the Republic party for being what they considered a race-baiter and trying to appeal to race hatred. It wasn’t long before he realized he would have to chart his own course if he hoped to continue working in politics. He began attacking what he considered machine politics which were exploiting Hispanic voters across New Mexico. His efforts forced both parties to begin acknowledging concerns of Hispanic New Mexicans. He garnered a reputation of someone who was not afraid to break with his party to protect Hispanic civil rights, and even campaigned for Hispanic candidates from both parties.

In 1919, despite his reputation for generating controversy, Larrazolo was elected the first Republican governor of New Mexico. As governor, he became a pioneer in the idea of public domain when he urged the national administration to cede unused federal lands to the states. He also passed measures that restricted child labor, mandated school attendance, raised the salaries of teachers, and ensured bilingual education was available in all New Mexican schools.

Larrazolo based his decisions on principle rather than partisan politics. He vetoed a resolution from his party to condemn President Woodrow Wilson’s call to create the League of Nations, and he adamantly supported the ratification of the 19th Amendment despite his core constituency opposing women’s suffrage. His principles, however, did not always please his party or constituents which ultimately led to him not being re-elected as governor.

After losing his re-election, Larrazolo went back to practicing law briefly in El Paso, but would find it difficult to stay away from politics for long. Within two years he returned to New Mexico and began speaking throughout the state. He would be elected to the state house of representatives in 1927, and continued to fight to address the same issues he originally fought for as governor including fighting for land ownership and land reclamation.

In 1928, Larrazolo was encouraged by a Republican colleague to run for a U.S. Senate seat that became vacant after the untimely passing of the incumbent senator. Although he was reluctant at first, he ultimately decided to run. He won the seat with 56 percent of the vote and became the first Hispanic Senator in American history. Sadly, he was diagnosed with the flu shortly into his term. Already suffering from poor health, he returned to New Mexico briefly. When he came back to Washington, he introduced a bill that would provide a military and industrial school for boys and girls in New Mexico. Unfortunately, his health continued to deteriorate, and in 1929 he returned to New Mexico for good. While there he suffered a stroke, and as his health issues continued, he passed away on April 7, 1930.

Lazzarolo eschewed party politics and followed his morals and principles. He was an ardent supporter of Hispanic rights and land reclamation, and built a reputation as a gifted orator. He often gave commencement speeches and questioned the “success” of men who had fame and fortune calling into question their means and methods. He was unafraid to question the status quo and to push for the things he believed in including equality.

Footnotes:

*At the time, much of what would be known as the western United States were territories of the US and had not been admitted into the Union as states.

**This was before the two major political parties in the United States realigned their beliefs and values

References:

“Finding Aid of the Octaviano A. Larrazolo Papers, 1841-1891 (bulk 1885-1930).” The University of New Mexico, University Libraries, Center for Southwest Research, https://web.archive.org/web/20210521161455/https:/rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmu1mss614bc.xml. Accessed 5 Oct. 2023.

“Larrazolo, Octaviano Ambrosio.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives, history.house.gov/People/Detail/15032401304. Accessed 5 Oct. 2023.

“Octaviano Ambrosio Larrazolo.” New Mexico History, newmexicohistory.org/2014/01/16/octaviano-ambrosio-larrazolo/. Accessed 5 Oct. 2023.